The Alchemist's Secret - Day 4: A Journey Through the Compiler

Day 4 of the Infineon course revealed the magic behind the curtain! With Boya Vinay Kumar, we dissected the compilation process, transforming human-readable C code into the raw binary that powers a microcontroller.

After building a solid foundation in computer architecture, Day 4 took us on a fascinating journey: the transformation of our C source code into a binary file that a processor can actually understand. Our guide for this deep dive into the compiler toolchain was Boya Vinay Kumar.

The Big Picture: From Text File to Executable

The journey from a .c file to a running program involves three main stages: Compilation, Linking, Flashing and Loading. Today, our focus was squarely on that first crucial step: Compilation. How does the elegant C code we write get turned into the ones and zeros of machine language?

The Tool for the Job: Cross-Compilation

In embedded development, we rarely compile the code on the target device itself. Instead, we use a cross-compiler. This is a special compiler that runs on our powerful host machine (like a Windows or Linux PC) but generates machine code for a completely different target architecture (like the ARM processor on our PSoC board).

We'll be using the industry-standard, open-source GNU Compiler Collection (GCC), specifically the ARM embedded toolchain. Another popular choice is the licensed Armcc compiler, but GCC is the powerful free option.

The Four Stages of Compilation

Compilation isn't a single monolithic step. It's a four-stage pipeline, and we can inspect the output at each stage. To see how it works, we used a simple project with three files: main.c, add.h, and add.c.

// main.c

#include "add.h"

#define red 01

#define blue 02

#define green 03

#define PI 3.14159

int gvar1;

int gvar3 = green;

const int gvar5 = 20;

void main() {

#if red == 01

gvar1 = add_two(5, red);

gvar1 += red + blue + PI;

#endif

while(1);

}

// add.h

int add_two(int x, int y);

int add_three(int x, int y, int z);

// add.c

#include "add.h"

int add_two(int x, int y){

return x+y;

}

int add_three(int x, int y, int z){

return x+y+z;

}

Stage 1: The Preprocessor (The Text Expander)

The first stop is the preprocessor. It's like a diligent assistant that prepares the code by handling all the directives that start with a # (called as marcos).

#include "add.h": It literally copy-pastes the entire content ofadd.hintomain.c.#define PI 3.14159: It performs a search-and-replace, substituting every instance ofPIwith3.14159.#if red == 01: It evaluates conditional compilation blocks, including or removing code based on the conditions.

We can tell the compiler to stop after this stage using the -E flag. The result is a .i file, which is just a massive, expanded C file.

arm-none-eabi-gcc -E main.c -o main.i

The following code is present in the main.i file:

// main.i

# 0 "main.c"

# 0 "<built-in>"

# 0 "<command-line>"

# 1 "main.c"

# 1 "add.h" 1

int add_two(int x, int y);

int add_three(int x, int y, int z);

# 2 "main.c" 2

int gvar1;

int gvar3 = 03;

const int gvar5 = 20;

void main() {

gvar1 = add_two(5, 01);

gvar1 += 01 + 02 + 3.14159;

while(1);

}

Decoding Our Toolchain: arm-none-eabi-gcc

This long name tells us everything about our compiler:

arm: The target processor architecture.none: It generates code for no specific Operating System (i.e., for bare-metal systems).eabi: Stands for Embedded Application Binary Interface, a standard that dictates how function calls, data types, and object files are structured.gcc: The GNU Compiler Collection.

Stage 2: The Compiler Proper (The Translator)

The expanded .i file is then fed to the compiler's core. This stage parses the C syntax and translates it into a lower-level, human-readable language: Assembly. The output is a .s file.

We can stop the process here using the -S flag:

arm-none-eabi-gcc -S main.i -o main.s

The following code is present in the main.s file:

// main.s

.cpu arm7tdmi

.arch armv4t

.fpu softvfp

.eabi_attribute 20, 1

.eabi_attribute 21, 1

.eabi_attribute 23, 3

.eabi_attribute 24, 1

.eabi_attribute 25, 1

.eabi_attribute 26, 1

.eabi_attribute 30, 6

.eabi_attribute 34, 0

.eabi_attribute 18, 4

.file "main.c"

.text

.global gvar1

.bss

.align 2

.type gvar1, %object

.size gvar1, 4

gvar1:

.space 4

.global gvar3

.data

.align 2

.type gvar3, %object

.size gvar3, 4

gvar3:

.word 3

.global gvar5

.section .rodata

.align 2

.type gvar5, %object

.size gvar5, 4

gvar5:

.word 20

.global __aeabi_i2d

.global __aeabi_dadd

.global __aeabi_d2iz

.text

.align 2

.global main

.syntax unified

.arm

.type main, %function

main:

@ Function supports interworking.

@ args = 0, pretend = 0, frame = 0

@ frame_needed = 1, uses_anonymous_args = 0

push {fp, lr}

add fp, sp, #4

mov r1, #1

mov r0, #5

bl add_two

mov r3, r0

ldr r2, .L3+8

str r3, [r2]

ldr r3, .L3+8

ldr r3, [r3]

mov r0, r3

bl __aeabi_i2d

adr r3, .L3

ldmia r3, {r2-r3}

bl __aeabi_dadd

mov r2, r0

mov r3, r1

mov r0, r2

mov r1, r3

bl __aeabi_d2iz

mov r3, r0

ldr r2, .L3+8

str r3, [r2]

.L2:

b .L2

.L4:

.align 3

.L3:

.word -133315785

.word 1075351804

.word gvar1

.size main, .-main

.ident "GCC: (Arm GNU Toolchain 13.2.rel1 (Build arm-13.7)) 13.2.1 20231009"

Stage 3: The Assembler (The Final Conversion)

The assembler takes the .s file and performs the final translation, converting the assembly mnemonics into pure binary machine code. The output is a .o file, also known as an object file. This file contains the raw instructions, but it's not yet executable—it's "relocatable," meaning the memory addresses for functions and variables aren't finalized yet.

We generate the object file using the -c flag:

arm-none-eabi-gcc -c main.s -o main.o

This object file contains raw machine code, but it's not something you can run or open on your host PC. Because it was built for the ARM architecture, your host machine (likely x86) won't understand it. If you tried to open the .o file in a text editor, you would just see unreadable characters, not clean 0s and 1s.

This is why the ARM toolchain provides a specific utility to see the contents of the .o file: the object dump tool (objdump). It knows how to parse the ARM ELF format and display its contents in a structured, human-readable way.

Peeking Inside the Object File

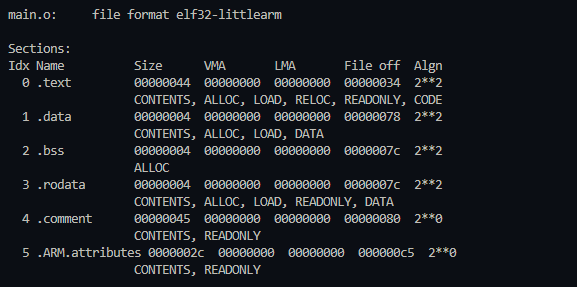

An object file is more than just code. It's organized into sections like .text (code), .data (initialized variables), and .rodata (constants). We can inspect these sections using another tool from our kit, objdump, the -h flag is used to display the section headers of the object file:

arm-none-eabi-objdump -h main.o

This command reveals the different sections and their sizes, giving us a glimpse into how our final program will be structured in memory.

Figure 1: Using objdump to see the internal sections of our compiled main.o file.

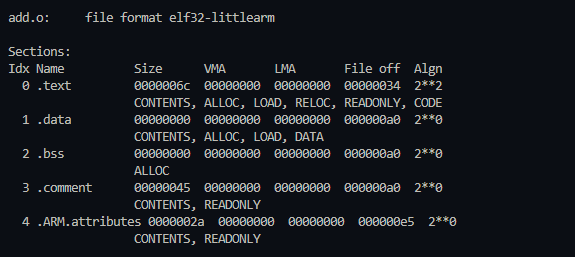

Figure 2: Using objdump to see the internal sections of our compiled add.o file.

This table shows us the different sections the compiler has created:

.text: Our executable code..data: Our initialized global variables..bss: Space reserved for our uninitialized global variables..rodata: Our constants.

Notice the VMA (Virtual Memory Address) and LMA (Loaded Memory Address) for all sections is 0x00000000. This confirms that the object file is relocatable—the final memory addresses haven't been assigned yet. That's the linker's job!

NOTE: The object file can directly be generated from the C source file in one step using:

arm-none-eabi-gcc -c main.c -o main.o

The intermediate steps are just for our understanding and debugging, as these files are generated internally.

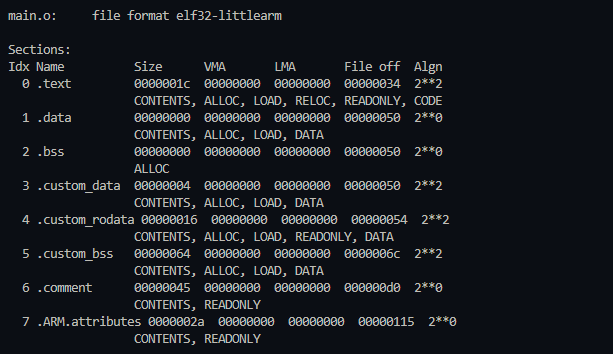

Taking Control: Creating Custom Sections

Beyond the standard sections, GCC gives us a powerful feature to define our own: the __attribute__ keyword. By specifying a section name, we can instruct the compiler to place specific variables into custom-named sections within the object file.

// main.c

int my_custom_data __attribute__((section(".custom_data"))) = 12345;

const char my_custom_rodata[] __attribute__((section(".custom_rodata"))) = "Hello Custom Section!";

char my_custom_bss[100] __attribute__((section(".custom_bss")));

int main() {

return 0;

}

Here's what this code does:

my_custom_data: This initialized global variable is placed into a new section named.custom_data.my_custom_rodata: This constant string is placed into a section named.custom_rodata.my_custom_bss: This uninitialized array is placed into a section named.custom_bss.

Figure 3: Using objdump to see the internal custom sections defined in our compiled main.o file.

This technique is incredibly useful for fine-grained memory management. Later, in our linker script, we can specifically target these custom sections and place them in precise memory locations, like a particularly fast SRAM or a protected memory region.

It's important to note that you cannot assign local (stack) variables to custom sections. This attribute only works for variables with static storage duration, such as global or static variables.

Specifying the Target CPU

When we compile, how does GCC know we're targeting the specific Cortex-M0+ core on our PSoC board and not some other ARM chip? We must explicitly tell it.

This is where a crucial compiler flag comes in: -mcpu. By adding -mcpu=cortex-M0plus, we instruct the compiler to generate machine code specifically tailored for the Cortex-M0+ instruction set. The complete and correct command for each source file looks like this:

arm-none-eabi-gcc -c main.c -mcpu=cortex-M0plus -o main.o

Each C file in our project (main.c, add.c, etc.) must be compiled this way into its own architecture-specific object file. Only once we have all our .o files, correctly built for our target, are we truly ready to hand them over to the linker.

The Missing Link

At the end of this process, we have main.o and add.o. But there's a problem: the machine code in main.o for the add_two() function call doesn't know where the actual code for that function is (it's in add.o). The two files are completely separate!

Resolving these cross-references and combining multiple object files into a single, final executable is the job of the Linker. It's the master architect that will take our compiled pieces and build them into one cohesive ELF (Executable and Linkable Format) file. But that... is a story for the next session!

#Infineon #EmbeddedSystems #Cohort3 #CProgramming #Compiler #GCC #ARM #BareMetal #Toolchain #SourceToBinary