The Master Blueprint - Day 5: Commanding the Linker

Day 5 of the Infineon course demystified the final step in our source-to-binary journey: linking! Guided by Prakash sir and Boya Vinay Kumar, we learned to write linker scripts to precisely control our program's memory map.

After mastering the art of compilation, Day 5 brought us to the final, crucial step: Linking. With Prakash sir and Boya Vinay Kumar at the helm, we moved from creating individual object files to assembling them into a single, cohesive executable. This is where we, the developers, take ultimate control of the machine's memory.

The Problem: A Pile of Bricks

The compiler left us with a set of object files (main.o, add.o, etc.). Each of these is a self-contained unit with its own .text, .data, and .bss sections. They are like neatly stacked piles of bricks, but they don't form a house yet. The instructions and data are ready, but they have no final home. This raises the critical question:

Where must these sections be stored in memory? What should their final addresses be?

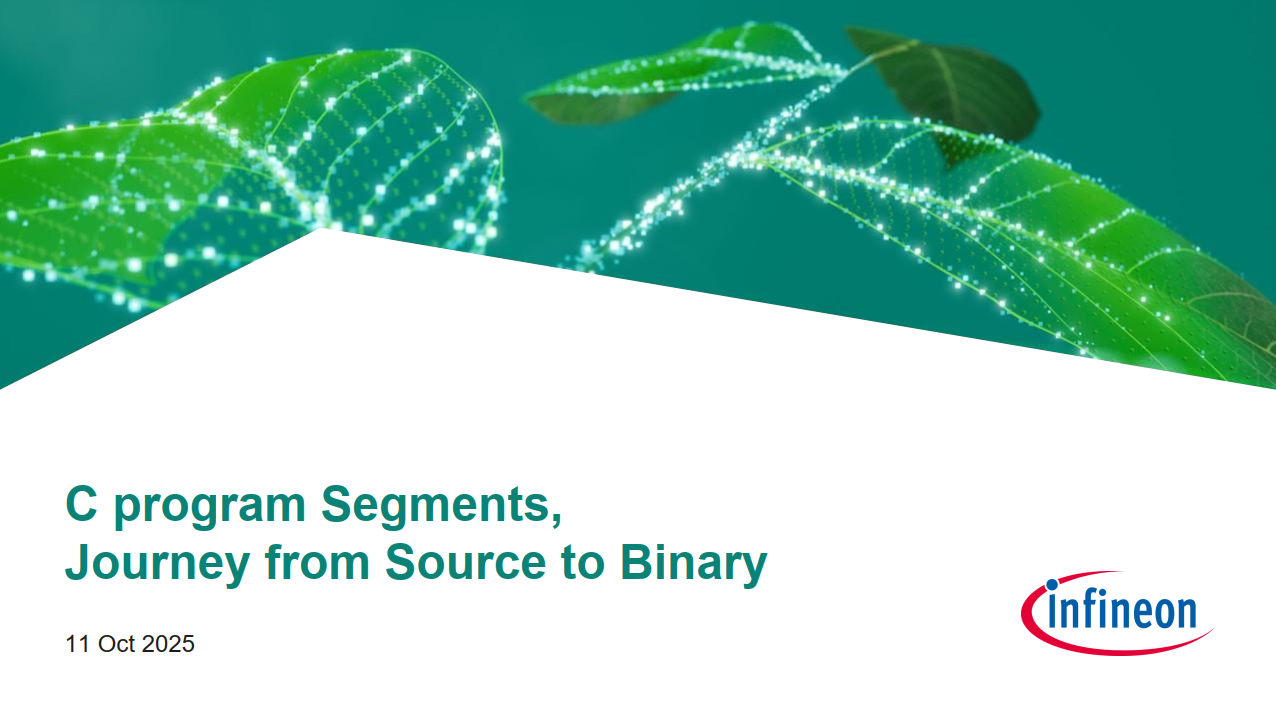

Figure 1: The linker acts as the master architect, assembling individual object files into a single, structured executable.

The Solution: The Linker and its Script

The Linker is the tool that solves this puzzle. It performs two primary jobs:

- Merging: It combines all the sections of the same type from different object files. For example, it takes the

.textfrommain.oand the.textfromadd.oand merges them into one large.textsection. - Memory Allocation: It assigns absolute memory addresses to all the merged sections, resolving any cross-references between the files.

But how does the linker know where to put everything? We tell it exactly what to do using a Linker Script. This script is our master blueprint, our masterplan, that dictates the final memory layout of our application. The linker just follows our instructions faithfully.

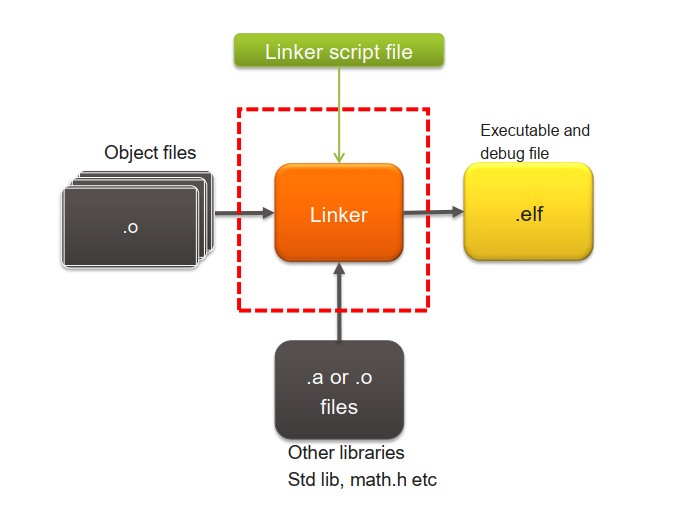

So, What is an ELF file Anyway?

Before we can write the script, we need to understand what we're building. The linker's output is an ELF (Executable and Linkable Format) file. This isn't just a raw dump of machine code; it's a sophisticated and standardized container. Think of it as a highly organized zip file for your program.

An ELF file contains several key parts:

- An ELF Header at the very beginning, which acts as a table of contents. It describes the file's architecture (e.g.,

elf32-littlearm), the entry point address where the CPU should start execution, and the locations of other important tables. - The actual program sections (

.text,.data,.bss, etc.). - A Section Header Table, which is a detailed list describing every single section: its name, size, location in the file, and attributes. This is what

objdumpreads to give us its output. - Debugging Information (like

.debug_frameand.debug_line_str), which maps the compiled machine code back to your original C source lines. This is what allows a debugger to let you step through your code line by line.

This structured format holds everything the system—whether it's an operating system loader or a hardware debugger—needs to know to correctly place your code in memory and execute it.

Figure 2: The organized structure of an ELF file, containing not just code, but also metadata for the loader and debugger.

The Linker Script: A Deeper Look

A GNU linker script has two main parts: the MEMORY block and the SECTIONS block. Let's build one for our microcontroller.

1. The MEMORY Block: Defining the Real Estate

First, we define the physical memory regions available on our chip. The syntax is MEMORY { name (attributes) : ORIGIN = start_address, LENGTH = size }.

MEMORY

{

FLASH (rx): ORIGIN = 0x00000000, LENGTH = 128K

SRAM (rwx): ORIGIN = 0x20000000, LENGTH = 16K

}

- The names

FLASHandSRAMare arbitrary; we could call themCODE_MEMandDATA_MEM. - The attributes define permissions:

r(read),w(write),x(execute). Our code in Flash can be read and executed, while data in SRAM can be read, written, and executed. LENGTHcan be specified in kilobytes (K) or as a hexadecimal value (128K is0x00020000).

2. The SECTIONS Block: Placing the Code and Data

This is where the magic happens. We define output sections, which are the new, combined sections that will exist in our final ELF file. Think of them as the destination folders.

Inside each output section, we specify which input sections should be placed there. The input sections are the original .text, .data, and .bss sections coming from our various object files (main.o, add.o, etc.).

We instruct the linker to gather all the input sections from all the object files and place them into the output sections we've defined.

SECTIONS

{

.code :

{

*(.text*)

*(.rodata*)

} > FLASH

.data :

{

*(.data*)

} > SRAM AT > FLASH

.bss :

{

*(.bss*)

} > SRAM

}

- The output section names like

.codeare custom. We could name it.my_awesome_codeif we wanted! - The

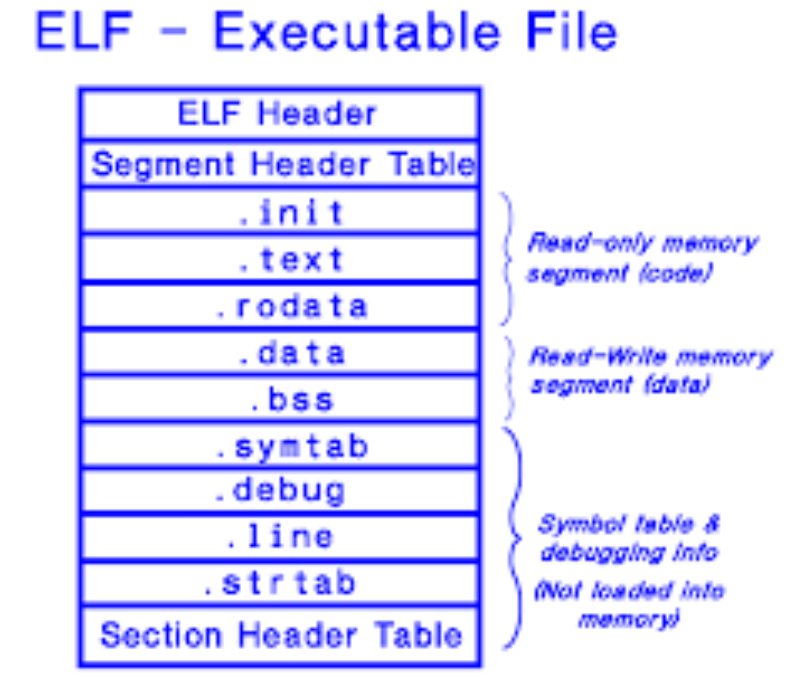

*(.text*)is a wildcard that tells the linker to grab the.textsection (and anything starting with.text, like.text.startup) from all input object files and place it here. - The VMA vs. LMA Trick: Look closely at the

.datasection!> SRAM: This defines the VMA (Virtual Memory Address). It tells the program that at runtime, this data will live in SRAM, where it can be modified.AT > FLASH: This defines the LMA (Load Memory Address). It tells the linker to physically place the initial values of the.datasection in the final binary file within theFLASHregion. This is a critical concept!

Figure 3: The .data section's values are loaded from Flash (LMA) to their runtime home in SRAM (VMA) by startup code.

Putting It All Together: From Linking to Running

With our linker script (linker.ld) ready, we can now invoke the linker through GCC:

arm-none-eabi-gcc -T linker.ld main.o add.o -nostartfiles -o application.elf

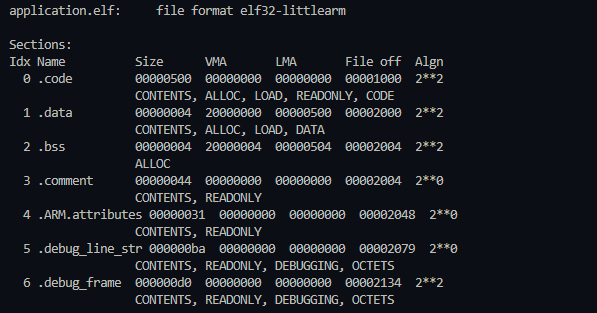

This command uses our script (-T linker.ld) to create the final ELF (Executable and Linkable Format) file. We can inspect this file to confirm our blueprint was followed:

arm-none-eabi-objdump -h application.elf

The output will now show our custom sections (.code, .data) with their final, absolute memory addresses assigned exactly as we specified. The output is a perfect reflection of our linker script:

Figure 4: The final ELF file's sections, now with absolute addresses assigned by the linker.

Let's break down the key sections:

.code: Its VMA and LMA are both0x00000000, the starting address of ourFLASHmemory region. This is exactly what we wanted for our code and read-only data..data: This is the most telling part! Its VMA is0x20000000, the start ofSRAM. However, its LMA is0x00000500. This confirms that the linker placed the initial values for the.datasection into the final binary file right after the.codesection (which had a size of 0x500 bytes)..bss: Its VMA is0x20000004, placed immediately after our.datasection inSRAM. Critically, it takes up no space in the file itself (its "File off" is the same as where.data's content ends). It's purely a memory reservation that our startup code will handle.

The linker has followed our commands perfectly, creating a file that is ready to be loaded onto our hardware.

So what happens when we power on the board? (to be explained in the upcoming classes)

- A small piece of startup code (which we'll explore later) begins to run.

- This code acts as a mover. It reads the initial values of the

.datasection from Flash (its LMA) and copies them to SRAM (its VMA). - It then clears out the

.bsssection in SRAM by writing zeros to it. - Finally, it jumps to our

main()function. - From this point on, the CPU fetches instructions (

.text) and constants (.rodata) directly from Flash, but reads and writes variables (.dataand.bss) from the much faster SRAM.

Day 5 was a true "level-up" moment, transforming us from mere code writers to architects of our system's memory. We've successfully crafted our master blueprint and commanded the linker to build the final executable file. But how can we prove it followed our instructions? The next logical step is to generate and analyze map files—the detailed reports that show exactly how the linker merged our sections and allocated every single byte. Once we've verified our blueprint, we'll be ready for the final stages in the upcoming classes: flashing our program onto the silicon and seeing it finally come to life!

#Infineon #EmbeddedSystems #Cohort3 #Linker #ELF #MemoryMap #VMA #LMA #BareMetal #Toolchain