The Awakening - Day 7: Startup Code and the Reset Sequence

Day 7 of the Infineon course answered the ultimate question: What happens before main()? We explored the Vector Table, the Reset Handler, and how the Linker Script orchestrates the initialization of memory.

We have compiled our code, linked our objects, and built our Makefiles. But on Day 7, Prakash sir and Ananth Kamath posed a fundamental question: When you plug in the power, how does the processor know where to begin?

It doesn't just magically jump to main(). There is a crucial sequence of events called the Startup Flow or Boot Firmware execution.

The First Breath: Reset

Before any code executes, the microcontroller goes through a Reset. This puts the hardware into a "Known State". Whether it's a Power-On Reset (POR) when we plug in the USB to hold the device while power ramps up, or a Software Reset triggered by code, the goal is to sanitize the registers and prepare the CPU.

When the reset signal is released, the ARM Cortex-M0+ processor automatically performs a specific hardware sequence:

- It fetches the Initial Stack Pointer (MSP) value from memory address

0x00000000. - It fetches the Reset Handler Address (the first instruction to run) from memory address

0x00000004and loads it into the Program Counter (PC).

This dedicated region of memory at the very bottom of the address map is called the Vector Table.

The Map to Survival: The Vector Table

The Vector Table is essentially an array of function pointers. It tells the CPU where to find the handlers for various system events (Exceptions) and hardware signals (Interrupts).

In our startup.c file, we defined this table explicitly. We used a special compiler attribute to place this array into a specific section named .isr_vector_section rather than the standard code section.

const uint32_t vector_table[48u] __attribute__((section(".isr_vector_section")))= {

STACK_START,

(uint32_t)&Reset_handler, /* Reset Handler */

(uint32_t)NMI_Handler, /* -14 NMI Handler */

(uint32_t)HardFault_Handler, /* -13 Hard Fault Handler */

(uint32_t)0, /* Reserved */

(uint32_t)0, /* Reserved */

(uint32_t)0, /* Reserved */

(uint32_t)0, /* Reserved */

(uint32_t)0, /* Reserved */

(uint32_t)0, /* Reserved */

(uint32_t)0, /* Reserved */

(uint32_t)SVC_Handler, /* -5 SVCall Handler */

(uint32_t)0, /* Reserved */

(uint32_t)0, /* Reserved */

(uint32_t)PendSV_Handler, /* -2 PendSV Handler */

(uint32_t)SysTick_Handler, /* -1 SysTick Handler */

/* Interrupts */

(uint32_t)ioss_interrupts_gpio_0_IRQHandler, /* 0 GPIO P0 */

(uint32_t)ioss_interrupts_gpio_1_IRQHandler, /* 1 GPIO P1 */

(uint32_t)ioss_interrupts_gpio_2_IRQHandler, /* 2 GPIO P2 */

(uint32_t)ioss_interrupts_gpio_3_IRQHandler, /* 3 GPIO P3 */

(uint32_t)ioss_interrupt_gpio_IRQHandler, /* 4 GPIO All Ports */

(uint32_t)lpcomp_interrupt_IRQHandler, /* 5 LPCOMP trigger interrupt */

(uint32_t)srss_interrupt_wdt_IRQHandler, /* 6 WDT */

(uint32_t)scb_0_interrupt_IRQHandler, /* 7 SCB #0 */

(uint32_t)scb_1_interrupt_IRQHandler, /* 8 SCB #1 */

(uint32_t)scb_2_interrupt_IRQHandler, /* 9 SCB #2 */

(uint32_t)scb_3_interrupt_IRQHandler, /* 10 SCB #3 */

(uint32_t)scb_4_interrupt_IRQHandler, /* 11 SCB #4 */

(uint32_t)pass_0_interrupt_ctbs_IRQHandler, /* 12 CTBm Interrupt (all CTBms) */

(uint32_t)wco_interrupt_IRQHandler, /* 13 WCO WDT Interrupt */

(uint32_t)cpuss_interrupt_dma_IRQHandler, /* 14 DMA Interrupt */

(uint32_t)cpuss_interrupt_spcif_IRQHandler, /* 15 SPCIF interrupt */

(uint32_t)csd_interrupt_IRQHandler, /* 16 CSD #0 (Primarily Capsense) */

(uint32_t)tcpwm_interrupts_0_IRQHandler, /* 17 TCPWM #0, Counter #0 */

(uint32_t)tcpwm_interrupts_1_IRQHandler, /* 18 TCPWM #0, Counter #1 */

(uint32_t)tcpwm_interrupts_2_IRQHandler, /* 19 TCPWM #0, Counter #2 */

(uint32_t)tcpwm_interrupts_3_IRQHandler, /* 20 TCPWM #0, Counter #3 */

(uint32_t)tcpwm_interrupts_4_IRQHandler, /* 21 TCPWM #0, Counter #4 */

(uint32_t)tcpwm_interrupts_5_IRQHandler, /* 22 TCPWM #0, Counter #5 */

(uint32_t)tcpwm_interrupts_6_IRQHandler, /* 23 TCPWM #0, Counter #6 */

(uint32_t)tcpwm_interrupts_7_IRQHandler, /* 24 TCPWM #0, Counter #7 */

(uint32_t)pass_0_interrupt_sar_IRQHandler, /* 25 SAR */

(uint32_t)can_interrupt_can_IRQHandler, /* 26 CAN Interrupt */

(uint32_t)crypto_interrupt_IRQHandler /* 27 Crypto Interrupt */

};

Placing the Map: The Linker's Role

Why did we need a special section name for the vector table? Because the hardware demands this table be at address 0x00000000. If it's anywhere else, the CPU won't find it upon reset. We enforce this placement in our Linker Script.

In the SECTIONS block of our linker script, we used the KEEP command to ensure the garbage collector doesn't remove this table (since no code explicitly calls it), and we placed it at the very top of the .text output section. Since the .text section is mapped to the start of FLASH (which starts at 0x00000000), this guarantees our vector table is the very first thing in the binary.

SECTIONS

{

.text :

{

KEEP(*(.isr_vector_section)) /* Keep the vector table */

*(.text*) /* All .text sections from input files */

*(.rodata*) /* All read-only data */

...

} > FLASH

...

}

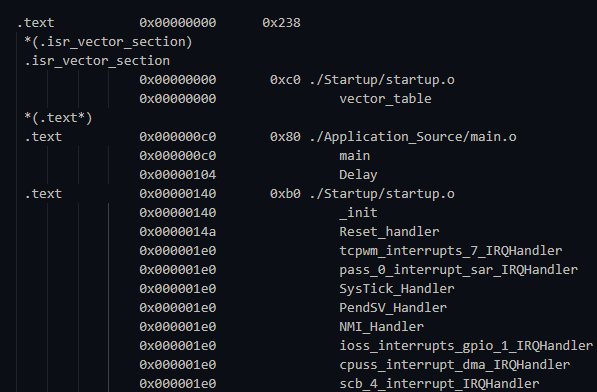

We verified this using objdump or the map file. The .text section starts exactly at 0x0, and the first symbol inside it is our vector_table.

Figure 1: Proof that our Linker Script successfully pinned the Vector Table to the start of Flash memory.

The Heavy Lifting: The Reset Handler

Once the CPU loads the PC with the address of the Reset_handler, our software finally takes control. But we can't call main() yet!

Why? Because main() expects a clean C environment:

- Initialized Globals: Variables like

int count = 5;must have their values ready. - Uninitialized Globals: Variables like

int buffer[10];must be zeroed out.

Right now, the values for our initialized variables are sitting in Flash (which is non-volatile and Read-Only). However, the variables themselves live in SRAM (which is Volatile and Read-Write) so they can be modified during execution. If we don't move the data, our variables will contain garbage.

Our Reset_handler performs this magic in three steps:

- Copy Data: It loops through the data stored in Flash (LMA) and copies it byte-by-byte to SRAM (VMA).

- Clear BSS: It loops through the BSS section in SRAM and writes zeros to every address.

- Init Library: It initializes the C Standard Library (LibC).

Only after these chores are done does it finally jump to the application's main() function.

void Reset_handler(void)

{

//disable watchdog

(*(uint32_t *) CYREG_WDT_DISABLE_KEY) = CY_SYS_WDT_KEY;

//copy .data section to SRAM

uint32_t size = &__data_end - &__data_start;

uint32_t *pDst = (uint32_t*)&__data_start;

uint32_t *pSrc = (uint32_t*)&_la_data;

for(uint32_t i = 0; i< size; i++)

{

*pDst++ = *pSrc++;

}

//int the .bss section to zero in SRAM

size = &__bss_end__ - &__bss_start__;

pDst = (uint32_t*)&__bss_start__;

for(uint32_t i = 0; i< size; i++)

{

*pDst++ = 0;

}

// Init C std libs

__libc_init_array();

//call main()

main();

while (1)

{

/* If main returns, make sure we don't return. */

}

}

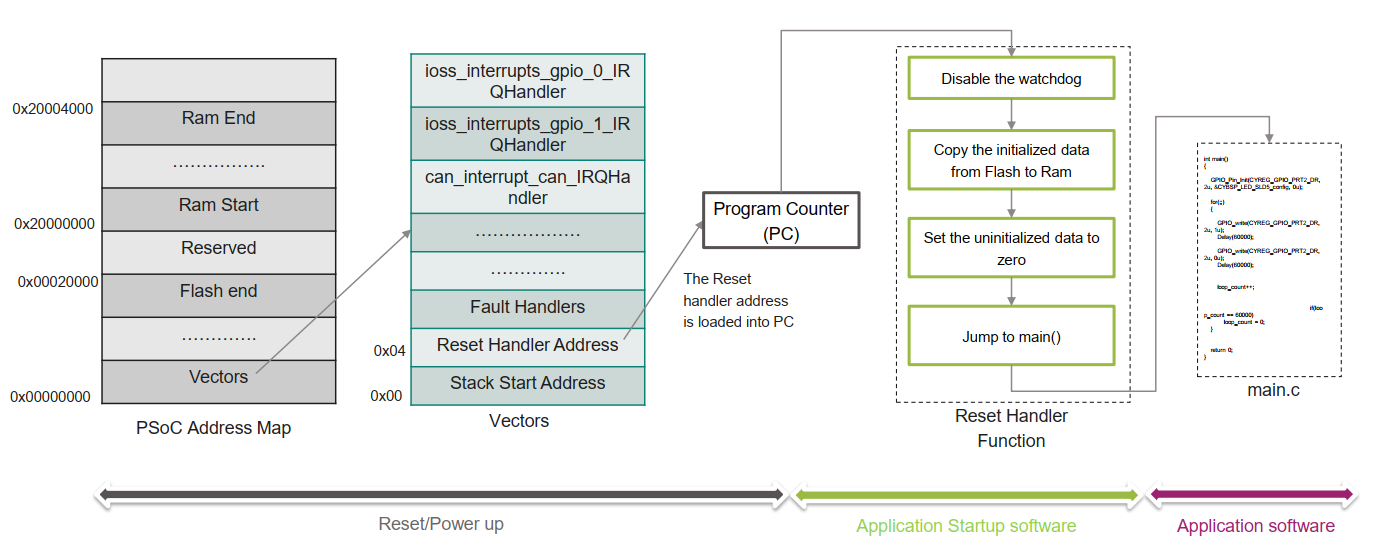

To visualize this entire journey—from the moment power is applied to the execution of your main function—here is the complete startup flow for our PSoC device:

Figure 2: The complete PSoC startup sequence. The diagram illustrates how the CPU fetches the Stack Pointer and Reset Handler from address 0x00 (left), and how the Reset Handler function (right) prepares the memory before handing control to the user application.

The Magic Markers: Linker Script Symbols

You might notice variables like &__data_start, &__data_end, and &_la_data in the C code loop. But we never declared them in our C files!

These are Linker Script Markers. We defined them inside the linker script to track the boundaries of our memory sections.

_la_data = LOADADDR(.data);

.data :

{

__data_start = .;

*(.data*)

. = ALIGN(4);

__data_end = .;

} > RAM AT> FLASH

_la_data(Load Address): Tells the C code where the data lives right now (in Flash).__data_start: Tells the C code where the data needs to go (in SRAM).

In our C code, we declare them as extern to tell the compiler, "Trust me, these exist; the linker will provide the address."

Crossing the Bridge: Introducing OpenOCD

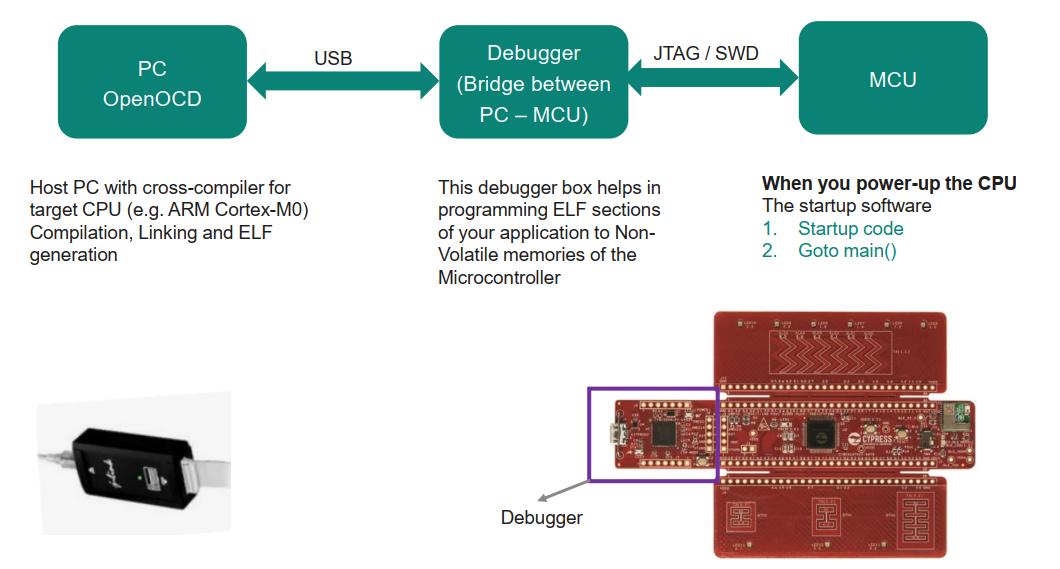

We've built the binary, but how does it actually get from our laptop to the silicon? Boya Vinay Kumar introduced us to the essential tool that bridges this gap: OpenOCD (Open On-Chip Debugger).

In our setup, the PC generates the ELF/Hex file. The PSoC board has a specialized chip on it called a "Debugger" or "Bridge" (specifically the KitProg3). OpenOCD is the software running on our PC that talks to this bridge over USB, allowing us to flash our program and debug it line-by-line.

Figure 3: The "Bridge" concept. OpenOCD allows our PC to communicate with the target MCU via the on-board debugger.

This is why our Makefile includes a specific path to the OpenOCD installation. We even added a specific Phony target called program:

# OpenOCD command to program the board

program: $(HEX)

$(OCD)/bin/openocd.exe -f $(OCD_Interface) -f $(OCD_Target) -c 'program $(HEX) verify reset exit'

Thanks to this setup, we don't need to open a separate programmer tool. We can simply type make program in our terminal. The Makefile will check if the code needs recompiling, build it, and then immediately launch OpenOCD to flash it onto the board. It is seamless automation at its finest!

Day 7 demystified the boot process. We learned that main() isn't the beginning, it's the destination. The journey involves a carefully choreographed dance between the Hardware Reset, the Linker Script's memory map, and the Startup Code's initialization logic.

#Infineon #EmbeddedSystems #Cohort3 #StartupCode #ResetHandler #VectorTable #LinkerScript #BareMetal #ARM