Debugging Mastery & The Art of Interrupts - Day 9: Interrupts and Exceptions - Part 2

We picked up right where we left off, diving deep into the micro-mechanics of how the Cortex-M0+ handles exceptions. From automatic stacking to the precise sequence of vector fetches, followed by hands-on interrupt coding with the BareMetal V2 project.

On Saturday, November 15th, 2025, we returned to the classroom with Siddhesh Raut and Prakash Balasubramanian to finish what we started: mastering Interrupts. After a quick recap of the NVIC and the basic concepts, we zoomed in to the nanosecond-level details of what happens when an interrupt strikes.

The Exception Entry Sequence

When an interrupt signal arrives (and makes it through all the enable gates), the CPU doesn't just instantly jump to the handler. It performs a carefully choreographed sequence of hardware operations to ensure it can safely return later.

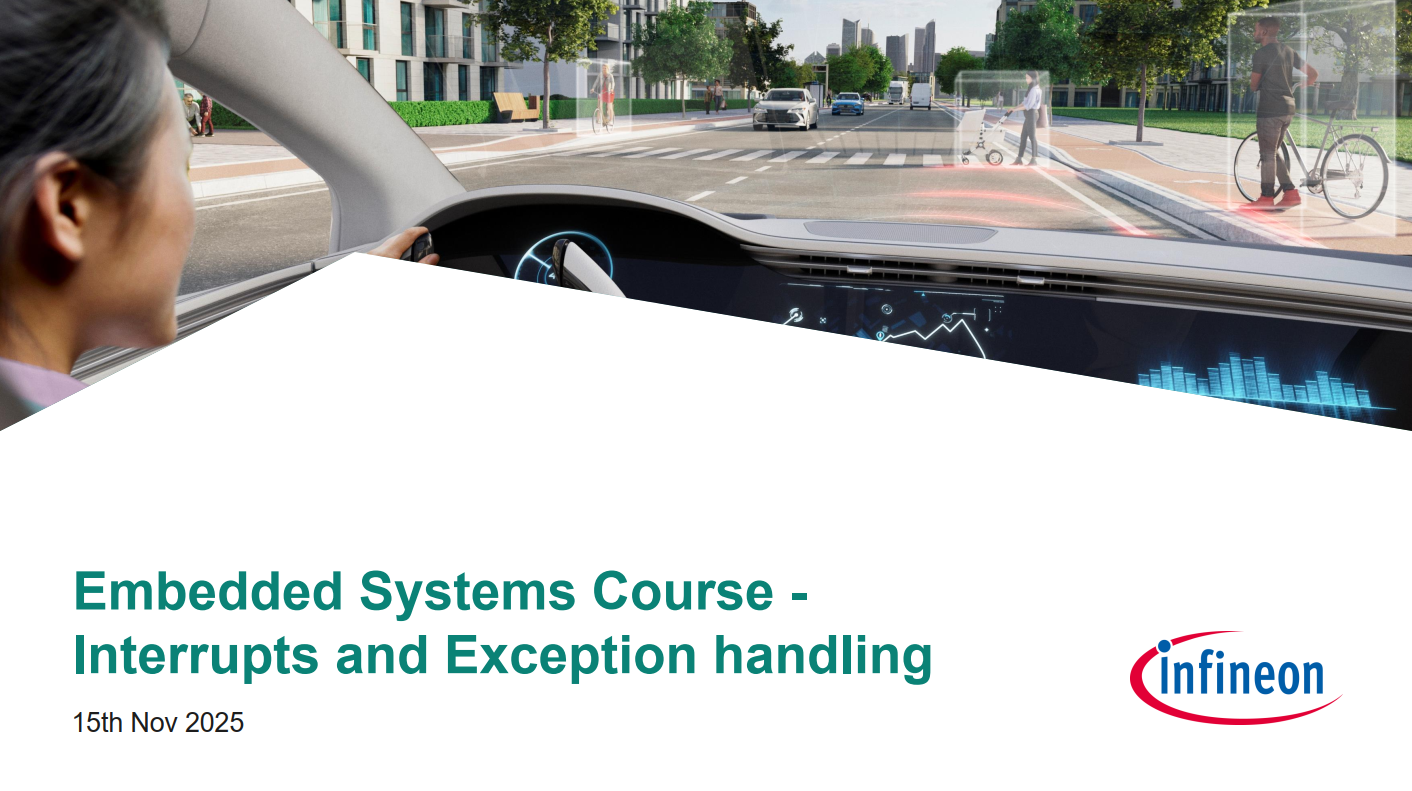

1. Stacking: Saving the Context

The CPU must save the state of the current task (Thread Mode) before switching to the interrupt (Handler Mode). This is called Stacking.

Ideally, we would save all 16 registers. But writing to memory takes time, and interrupts need to be fast (low latency). So, the hardware automatically pushes only a specific subset of 8 registers onto the stack:

- R0 - R3: The "scratch" registers used for passing arguments.

- R12: Another scratch register.

- R14 (LR): The Link Register.

- Return Address (PC): Where we were executing code.

- xPSR: The Program Status Register.

Why these 8? Because the ARM Procedure Call Standard (AAPCS) dictates that these are the registers a called function (or ISR) is allowed to overwrite without asking. The other registers (R4-R11) are "callee-saved," meaning if the ISR needs to use them, it's the ISR's software responsibility to push them first. This hardware optimization keeps interrupt entry lightning fast.

Figure 1: The hardware automatically saves the critical "caller-saved" registers to the stack to preserve the current program state.

2. Vector Fetch & Update PC

While the stacking is happening (in parallel, thanks to the hardware pipeline!), the processor fetches the starting address of the ISR from the Vector Table. It loads this address into the Program Counter (PC), effectively jumping to the handler.

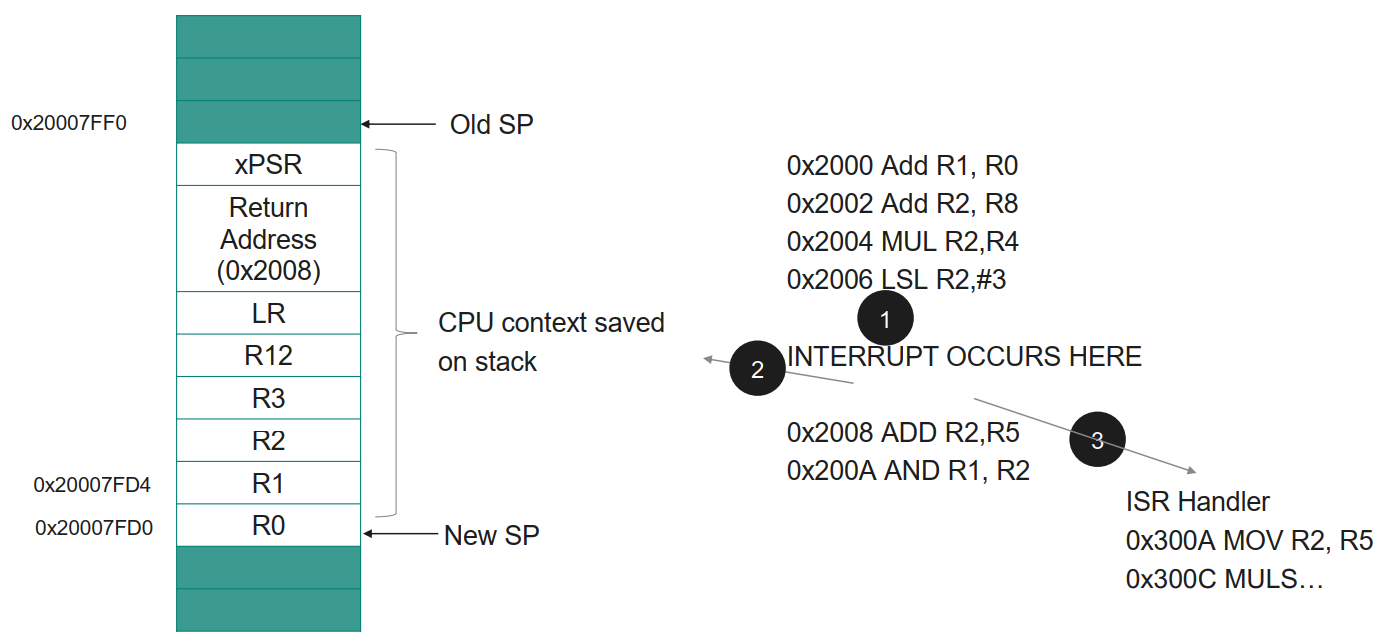

3. Execution & Unstacking

The CPU executes the ISR code. When it finishes, it doesn't just "return". It performs an Unstacking sequence. It pops the saved values from the stack back into the registers, restoring the CPU to the exact state it was in before the interruption. To the main program, it looks like nothing ever happened!

Figure 2: The hardware automatically restores the critical "caller-saved" registers from the stack to preserve the previous program state.

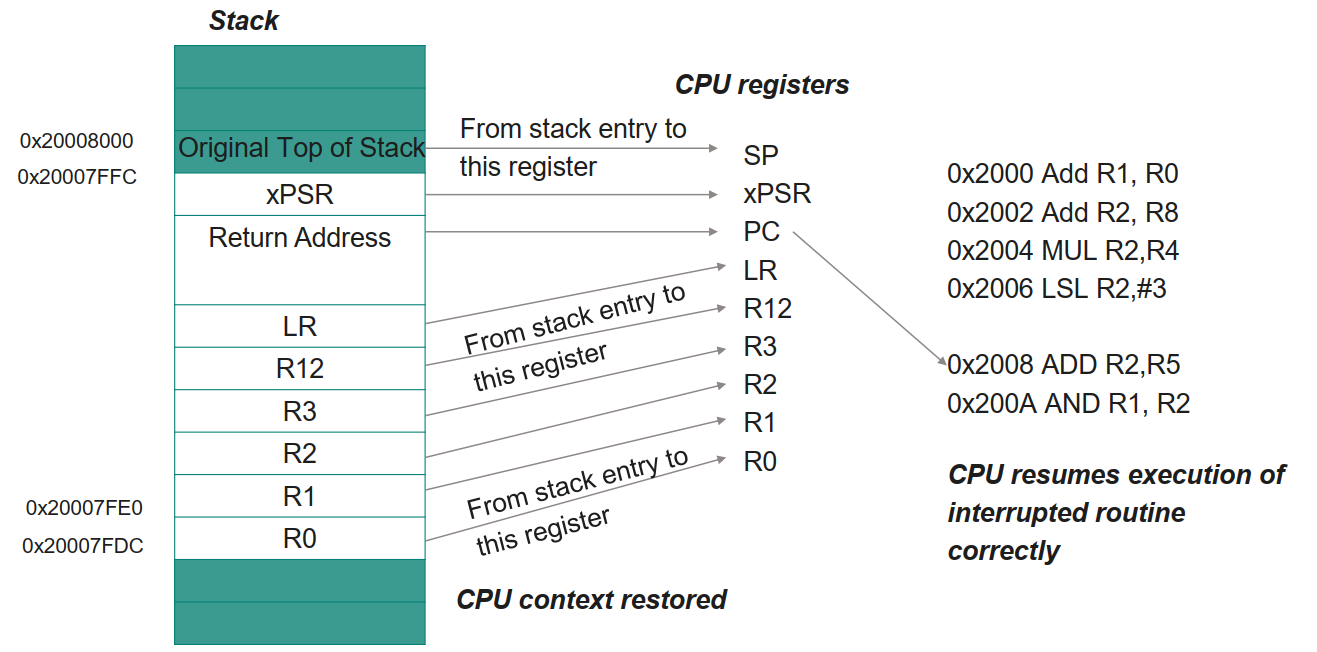

To visualize this entire flow—from the hardware signal assertion to the return to normal execution—here is the complete interrupt timeline:

Figure 3: The complete lifecycle of an interrupt. The diagram highlights the transition from Thread Mode to Handler Mode, the automatic clearing of the pending bit, and the critical Stacking/Unstacking phases.

Key Takeaways: Managing Interrupts

We then solidified our understanding by solving practical configuration scenarios for the NVIC.

1. Setting Priorities: The IPR Registers

We learned that to prioritize interrupts, we program the Interrupt Priority Registers (IPR). Each IRQ has a specific 2-bit field within these 32-bit registers.

- The Challenge: We wanted to set IRQ-14 to the highest priority (0) and IRQ-5 to a lower priority (2).

- The Solution: First, we identified that IRQ-5 lives in IPR1 and IRQ-14 lives in IPR3. We then shifted our priority values into these specific positions.

// Set IRQ-5 to Priority 2 (IPR1)

*((uint32_t *)0xE000E404) = (2U << 14);

// Set IRQ-14 to Priority 0 (IPR3)

*((uint32_t *)0xE000E40C) = (0U << 22);

2. Enabling and Disabling: SETENA & CLRENA

To control interrupts at runtime, we use SETENA (Set Enable) and CLRENA (Clear Enable). Since these are "Write 1 to Enable/Disable" registers, we can control multiple interrupts in a single instruction without affecting others.

- The Challenge: Enable IRQ-5, IRQ-8, and IRQ-9 simultaneously.

- The Solution: We constructed a bitmask with 1s at positions 5, 8, and 9 and wrote it to the SETENA address (

0xE000E100).

// Enable IRQ-5, 8, and 9

*((uint32_t *)0xE000E100) = (1U << 5) | (1U << 8) | (1U << 9);

3. Pending & Active Status

Finally, we explored how to check the system's state using SETPEND (to check/force pending status) and IPSR (to check active status).

- Checking Pending: Reading

SETPENDgives us a 32-bit mask of all interrupts waiting to run. We can even force an interrupt by writing a1to its bit position in this register. - Checking Active: To know exactly which ISR is currently executing, we read the IPSR (Interrupt Program Status Register). The lower 6 bits represent the Exception Number:

- 0: Thread Mode (No active interrupt).

- 16: IRQ-0 is active.

- 19: IRQ-3 is active. (Note: The IRQ Number is simply the Exception Number minus 16).

Hands-On: BareMetal V2 & The GPIO Interrupt

Today's hands-on was started by flashing our boards with the BareMetal V2 project. The goal? To toggle an LED using a button press, but this time using an Interrupt instead of polling.

Note: While we are using GPIO functions to read the button and toggle LEDs, don't worry if the GPIO configuration details seem complex right now. We will have a dedicated deep-dive into GPIO architecture in the upcoming classes. For today, our primary focus is on the Interrupt mechanism itself.

The main.c Logic

In our main() function, we performed the standard initialization:

- Init GPIO: We configured the LED pins as outputs and the Switch pin as an input.

- Enable Interrupts: We used

NVIC_EnableIRQ(3u)to turn on IRQ #3. Why #3? Because looking at the PSoC architecture, the GPIO Port 3 interrupt line is connected to IRQ #3. - Set Priority: We set its priority to 1 (high urgency).

Then, we dropped into an infinite loop for(;;) that just blinks another LED. This proves that the CPU is busy doing "normal work".

int main()

{

// Enable Global Interrupts at CPU level (PRIMASK)

enable_irq();

// 1. Initialize GPIOs

// LED10 on Port 2.2, Switch on Port 3.7

GPIO_Pin_Init((GPIO_PRT_Type *)CYREG_GPIO_PRT2_DR, 2u, &LED10_P2_2_config, HSIOM_SEL_GPIO);

GPIO_Pin_Init((GPIO_PRT_Type *)CYREG_GPIO_PRT3_DR, 7u, &SW2_P3_7_config, HSIOM_SEL_GPIO);

// ... init other LEDs ...

// 2. Configure NVIC for IRQ #3 (GPIO Port 3)

NVIC_SetPriority(3u, 1u); // Set Priority to 1 (High)

NVIC_ClearPendingIRQ(3u); // Clear any pending noise

NVIC_EnableIRQ(3u); // Enable IRQ #3 at NVIC level

for(;;)

{

// Background task: Blink LED10 endlessly

// This proves the CPU is busy doing "normal" work

GPIO_write((GPIO_PRT_Type *)CYREG_GPIO_PRT2_DR, 2u, 1u);

Delay(60000);

GPIO_write((GPIO_PRT_Type *)CYREG_GPIO_PRT2_DR, 2u, 0u);

Delay(60000);

}

return 0;

}

The Interrupt Handler

We defined a specific function: void ioss_interrupts_gpio_3_IRQHandler(void) as shown below.

// This function name matches the Vector Table entry exactly

void ioss_interrupts_gpio_3_IRQHandler(void)

{

// 1. CRITICAL: Clear the interrupt at the Peripheral level

// If we skip this, the interrupt line stays high, and the ISR loops forever!

GPIO_ClearInterrupt((GPIO_PRT_Type *)CYREG_GPIO_PRT3_DR, 7u);

// Simple debounce

Delay(20000);

// 2. Handle the Logic (Toggle another LED based on flag)

if((GPIO_Read((GPIO_PRT_Type *)CYREG_GPIO_PRT3_DR, 7u) == 0u)) // Check if pressed (Active Low)

{

if(invertFLAG == 1u)

{

GPIO_write((GPIO_PRT_Type *)CYREG_GPIO_PRT1_DR, 6u, 1u); // Turn LED ON

invertFLAG = 0u;

}

else

{

GPIO_write((GPIO_PRT_Type *)CYREG_GPIO_PRT1_DR, 6u, 0u); // Turn LED OFF

invertFLAG = 1u;

}

}

}

Crucially, this exact function name is listed in our startup.c file inside the Vector Table as shown below. When IRQ #3 fires, the hardware looks up this specific address and jumps here.

// In startup.c, inside the Vector Table definition:

const uint32_t vector[48u] __attribute__((section(".isr_vector")))= {

(uint32_t)&__stack_Start__,

(uint32_t)Reset_handler,

// ... System Exceptions ...

/* Interrupts (External IRQs) */

(uint32_t)ioss_interrupts_gpio_0_IRQHandler, /* 0 GPIO P0 */

(uint32_t)ioss_interrupts_gpio_1_IRQHandler, /* 1 GPIO P1 */

(uint32_t)ioss_interrupts_gpio_2_IRQHandler, /* 2 GPIO P2 */

(uint32_t)ioss_interrupts_gpio_3_IRQHandler, /* 3 GPIO P3 <--- Hardware jumps here! */

// ...

};

Inside the handler:

- Clear Interrupt: We immediately clear the interrupt flag on the GPIO port using

GPIO_ClearInterrupt. If we forget this, the interrupt will fire again endlessly! - Logic: We read the switch status. If pressed, we toggle a flag variable and change the state of an LED.

This simple example demonstrated the power of asynchronous events. The main loop keeps blinking its LED, completely unaware that a button press occurred, until the ISR gracefully interrupts it, handles the button, and returns control.

A Final Note: The Trade-off of Optimization

Before wrapping up Day 9, we touched upon a critical setting in our build process: Compiler Optimization.

When we write C code, the compiler translates it into assembly. But how it translates can vary wildly based on our goals. Do we want the code to be as small as possible? As fast as possible? Or do we want it to be easy to debug?

The GCC compiler offers several Optimization Levels (-O), which we can set in our Makefile's CFLAGS.

-O0(No Optimization): This is the default for debugging. The compiler does exactly what you wrote. Variables are kept in memory, and code structure is preserved. This makes stepping through code with a debugger predictable and easy. This is what we use in our course.-O1(Optimize): The compiler tries to reduce code size and execution time without taking too long to compile.-O2(Optimize More): A balanced approach for release builds. It performs nearly all supported optimizations that don't involve a space-speed tradeoff.-O3(Optimize Heavily): Focuses purely on speed. It might unroll loops or inline functions aggressively, potentially making the binary larger.-Os(Optimize for Size): The gold standard for memory-constrained embedded systems. It enables all-O2optimizations that don't increase code size.

In our current project, you can see the flag set to -O0 in the CFLAGS variable:

CFLAGS = $(DFLAGS) -g -c -Wall -Wextra -std=gnu11 -O0 -DSEMIHOSTING=$(SEMIHOSTING)

We use -O0 because debugging optimized code can be a nightmare—lines of code might be skipped, reordered, or variables might be "optimized away" entirely, making them invisible to the debugger!

#Infineon #EmbeddedSystems #Cohort3 #Interrupts #CortexM0Plus #NVIC #Stacking #BareMetal #GPIO